Why the 3 Digits on the Back of Your Credit or Debit Card Matter

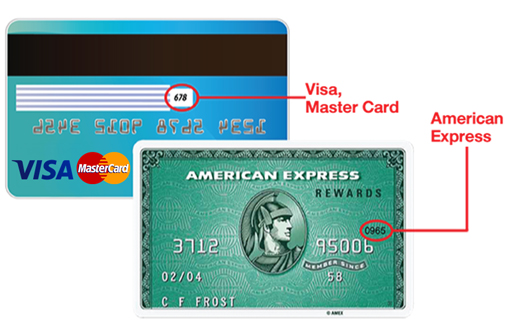

The three digits on the back of a credit/debit card (CVV2, which I will refer to as CVV), provide some assurance to a merchant and bank/card issuer that a given credit/debit card is physically present with the purchaser, in what is known as a card-not-present transaction; for example, online or over the phone transactions.

Within modern cards there is another CVV (CVV1) stored in the magnetic stripe. This is different from the three digits that are printed on the back of the card, although it is calculated in a similar way. This means that if a card is cloned from the magnetic stripe by an ATM or similar, an adversary still does not have all of the information that they need to make a card-not-present transaction.

In addition, CVV numbers are not legally able to be stored by merchants which adds another degree of security. If a merchants card transaction database were to be compromised, even though an adversary would have access to the long card numbers (PANs) and corresponding expiry dates, they still don’t have the CVV numbers and so the data they do have is less useful. Further to this, it also protects consumers against insider threats within merchant organisations; insiders may have legitimate access to the same card transaction database but also, do not have access to the CVV.

Finally, due to the strong encryption algorithm (2TDES - I’ll do a future post on the generation of CVV numbers) that is used in the CVV generation process, an adversary is not able to calculate the CVV number; this is assuming that the two encryption keys used remain secret. Therefore, an adversary would have to either try to brute force the CVV or obtain it in some other way, both adding a degree of difficulty for an adversary. In particular, a brute force attack on CVV numbers would likely be detected by the card issuer and would result in the card being blocked.